Praxis – Mapping Geographies of Self

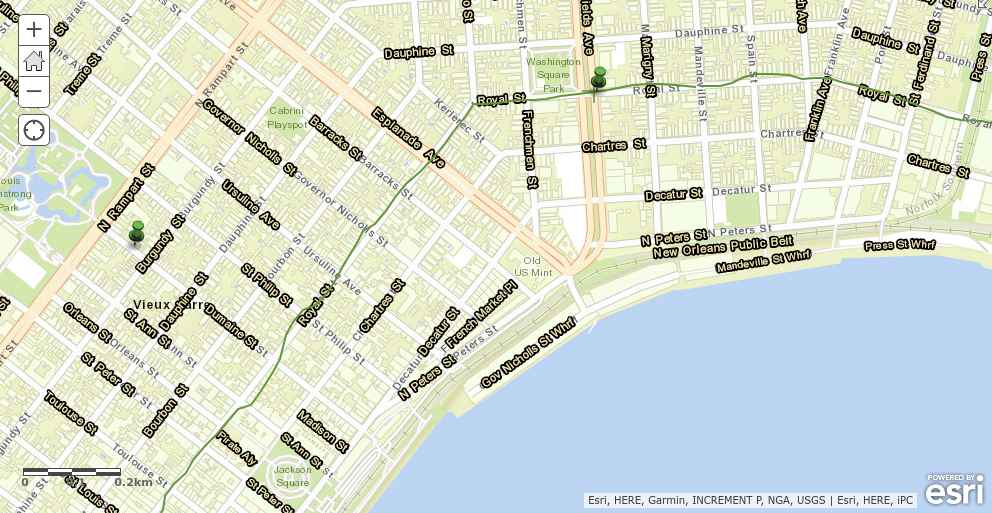

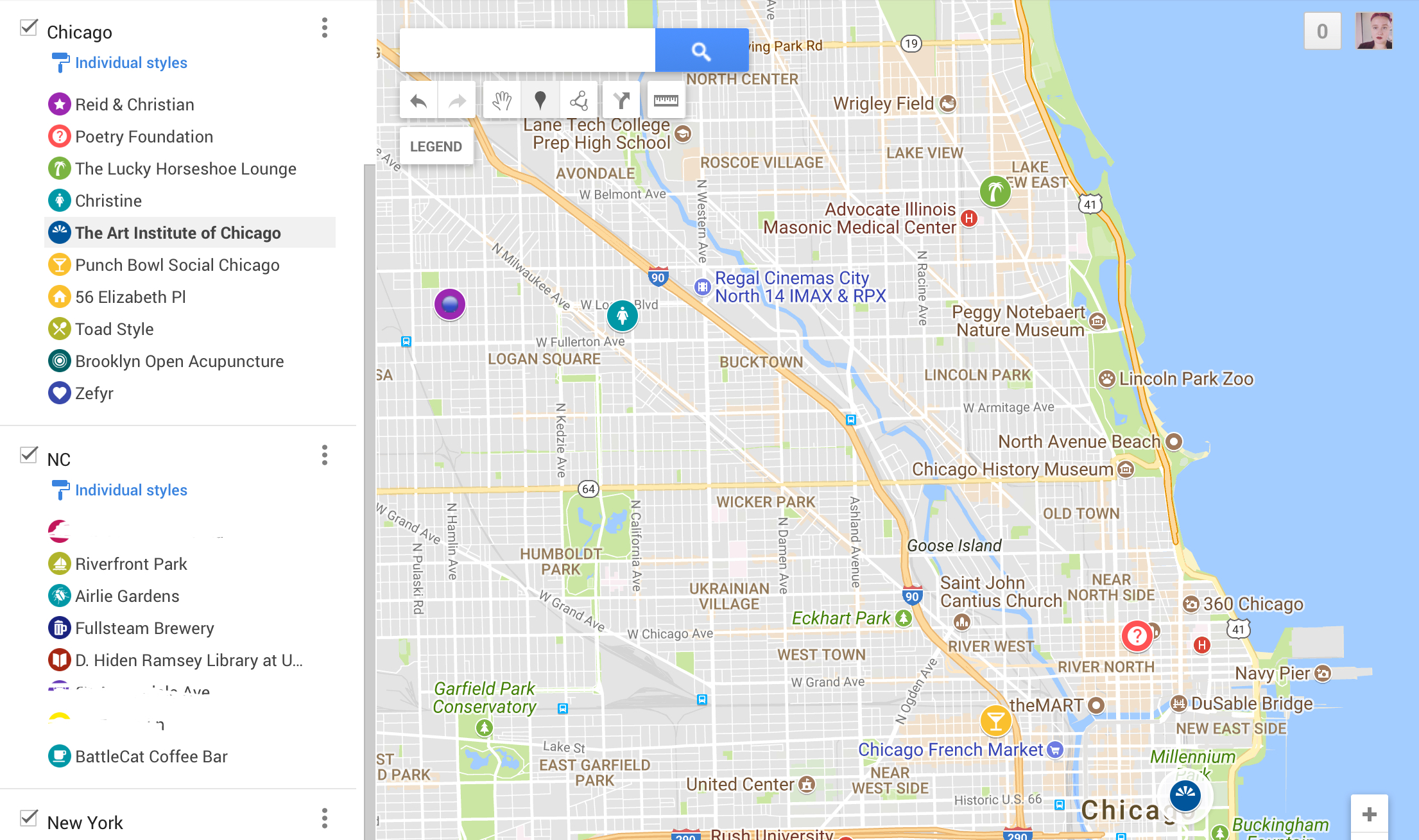

For this praxis assignment, I chose to work with Google Maps. I am already experienced with the platform, and the other suggested mapping softwares seemed intimidating on top of the abundance of other stuff I had to do over the past two weeks, so Maps was a perfect choice. I’ve actually been working on mapping locations where I work on my new writing project: a collection of autotheoretical short prose essays on chronic pain and embodiment. This project gave me the actual push I’ve needed to digitalization my lo-fi mapping (writing down lists of places I work in my phone).

As I develop notes towards my dissertation, I am embracing the role my own body plays in my writing and reading practices more and more. It seems silly to write about embodiment in any sort of abstracted way since the body is the thing doing the work of writing and theorizing. The weirdness appears in figuring out the relationships between and among the body and disembodied sites of writing and practice, like digital spaces. This mapping gave me a needed opportunity to start tracing a visual-spatial trail of how I move through 3D geographies while contributing to my ongoing move towards digitalizing my notes in readable forms.

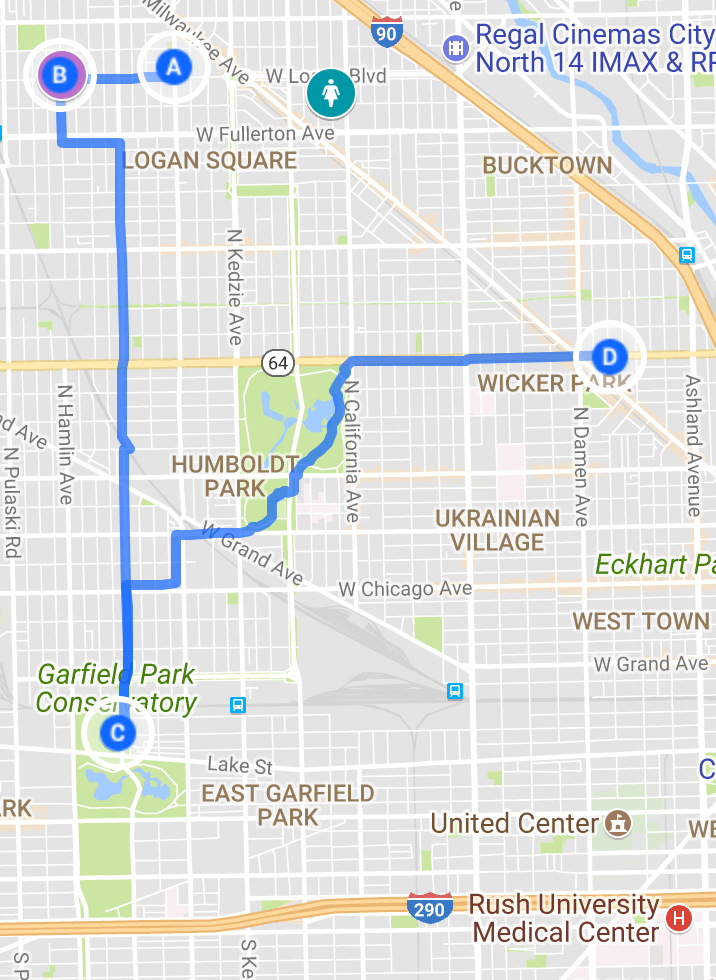

Since I was stuck an extra day in Chicago, I decided to add locations where I had been on email, writing, reading, doing homework assignments, or otherwise “laboring” while in town. (This is also maybe revelatory of my reframing of “work” to shake off a long time on shift schedules, and to provide evidence that being an adjunct/“funded” graduate student means *never not working*.) Next, I’m adding layers of commuting and travel maps to make visible my movement around the city by car and train and walking—I haven’t yet figured out how to express that which choice I make depends largely upon my health at that moment, or anticipating my health later in the day.

Maps doesn’t make it easy to input actual circuitous routes, as it automatically adjusts the routes to highlight the fastest way from point to point, which isn’t actually always the way we went. That aside, though, I like this feature, and I know of accessibility scholars who have taken up adding notes of locations of curb cuts and other accessibility markers.

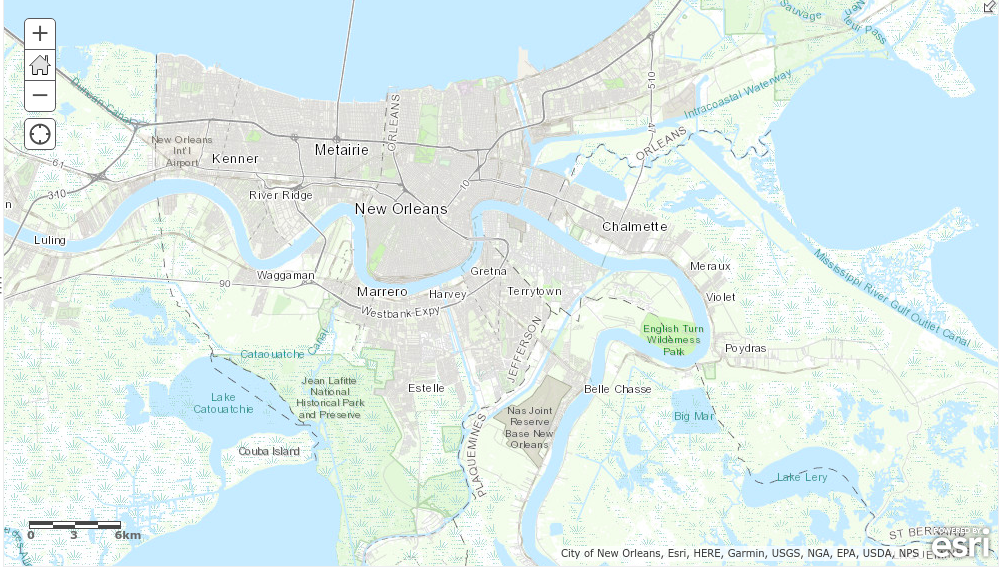

I also tried to implement this mapping strategy across my home state of North Carolina, which I visit about once a year, but the much larger scale made mapping less effective:

I’d like to figure out more intuitive ways to trace movement, but I do appreciate that I could demarcate each location with a customized icon and color. I don’t really understand why my own maps aren’t integrated with my use of the Google Maps app, but I’m also iffy about all my data being used everywhere!