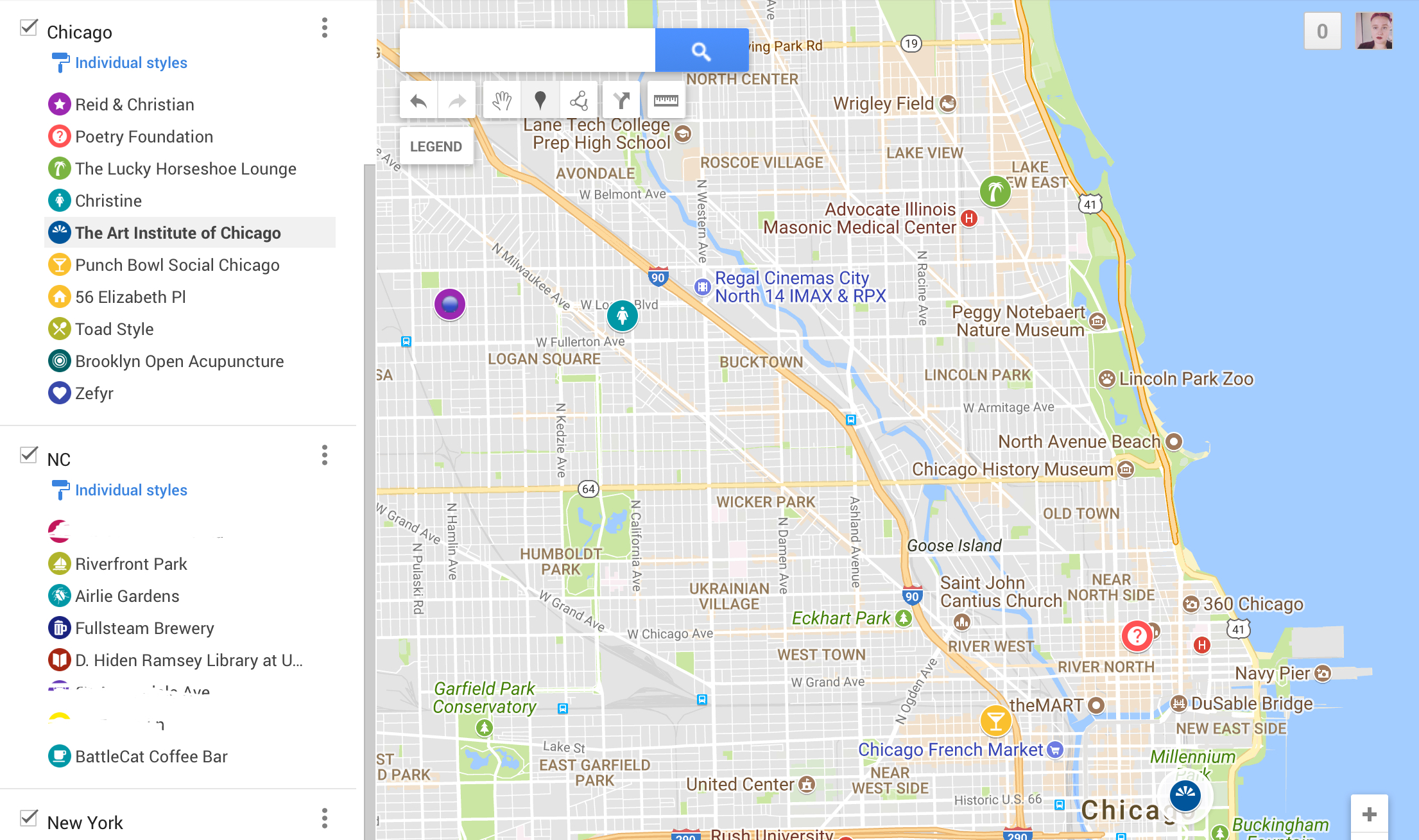

Approaching the Digital Humanities

ENGL 89500: Spring 2018 – CUNY Graduate Center

Professor Matthew gold

Annotated Bibliography: 5/1/18

Keywords:

Mediation

Materiality

Information

Control

Media Archaeology

Future of the Book

Orality

Project Idea: Tool that helps bolster memory for oral transmission of texts that utilizes deformance methodologies – Enhanced Orality

Human body as infrastructure for information preservation/dissemination

Works Cited

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter a Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press, 2010.

Bennett’s argues in her compelling monograph Vibrant Matterthat political and social theory often disregards the nonhuman forces that shape events. She conceptualizes a “vital materiality” that works from within and without, through and across bodies, both human and non-human. Agency emerges, she argues, as a result of the effects of an “ad hoc configuration of human and nonhuman forces”. In political analysis we often favor the impact of the human, disregarding altogether the impact that objects and materials have on the playing out of political events. She constructs theoretical implications of her vital materialism by deftly examining a variety of recognizable, common things (stem cells, fish oils, electricity, metal, and trash). By engaging with historical concepts from a range of philosophers and thinkers (Spinoza, Nietzsche, Darwin, and Adorno to name a few) she discloses the makings of a robust historical framework for thinking about matter vibrantly. Although her book is ultimately a political one, it has a range of applications for the study of materiality within the digital humanities. I intend to examine her theories concerning their implications for media archaeology and the future of the book.

Boissoneault, Lorraine. “A Brief History of Book Burning, From the Printing Press to Internet Archives.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 31 Aug. 2017, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/brief-history-book-burning-printing-press-internet-archives-180964697/.

In her article “A Brief History of Book Burning, From the Printing Press to the Internet Archives,” Boissoneault quotes John Milton, “’Who kills a man kills a reasonable creature… but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself—’”. Boissonealt examines the history of book burning and the potential for digital technology to prevent the reoccurrence of similar events. The main thrust of her article compares the contextual circumstances that lead to historically noteworthy instances of mass book burning, and the impact that technology has had and may still have on book burning’s significance. The introduction of the printing press allowed for the mass proliferation of books, thereby mostly preventing full erasure of the book artifact. However, she points out, that even when knowledge itself isn’t prevented from reaching the public, the symbolic weight of book burning is dangerous in its own right (i.e. the famous Nazi book burnings in the late 1930’s). Digital technology and the internet seem to offer books a potential immortality. However, Boissoneault points out that hardware and software obsolescence, along with concerns around server space constraints problematize that potential. The article argues that the core motivations for book burning historically, as well as in our networked digital age remain the same: “prioritizing one type of information over another.” As we theorize the future of the book, we must come to terms with this reality, and anticipate new formal inoculations against the future of book burning.

Frow, J. (2001). A pebble, a camera, a man who turns into a telegraph pole. Critical Inquiry, 28(1), 270-285.

What makes complex objects more than a bag of parts? In “A pebble, a camera, a man who turns into a telegraph pole” John Frow lays out a subtle yet critical meditation on things. I see this piece as a complimentary article to Roland Barthes Camera Lucidawhereby Barthes examines the subject of the photograph, as well as the experience of looking at photos, Frow takes a look at the camera as artifact, and how it relates to the infrastructure that gives it meaning. He doesn’t limit himself to the camera. He turns his gaze to simple natural objects as well, like a pebble, and examines its thingness in an attempt to draw out a potential world where “persons and things are partly strangers and partly kin.” (276) This work, in contrast to Jane Bennett’s “Vibrant Matter” attempts an examination of objects and materials that focuses on an individuation that frees things from “instrumental status.” (277) He examines different models of ontology, actor network theory, Gadamer’s definition of things against use, as well as the status of the work of art. The political economies of Marx and Hurkheimer, as well as the poetry of Rilke and Herbet Zbigniew, lay groundwork for this critical inquiry into the nature of “thingness”.

Gabrys, Jennifer. Digital Rubbish: a Natural History of Electronics. University Of Michigan Press, 2013.

In Digital Rubbish Jennifer Gabrys examines the material life of information in the electronic age. She studies the infrastructure of information devices, their life and afterlife with a cultural material mapping of the spaces and trajectories of how hardware, and the information within, accumulate, breakdown, are preserved, and pass away. This study largely ignores the popular green conscious focus on “digital” infrastructure’s immateriality. She explores 5 interrelated “spaces” that make up a robust infrastructure of materiality: Silicon Valley, Nasdaq, Containers bound for China, Museums and Archives that preserve obsolete electronics, to the obsolescent repository that is represented by the rubbish landfill. When considering the mechanisms, infrastructures, networks, and power players that control information, it’s necessary to take a deep dive into the ways material impacts the equation. I plan to engage this text from the perspective of “vibrant matter” ala Jane Bennett and consider infrastructure as a key player in the future of scholarly communications.

Gleick, James. The Information: a History, a Theory, a Flood. Fourth Estate, 2012.

In The Information, James Gleick tackles the subject of information broadly, and how it has transformed the nature of human consciousness. This is a historical journey through the archives of communication and information sharing. Gleick tackles the subject in broad strokes by interrogating a variety of communication mediums, some familiar, others more exotic, including the language of Africa’s talking drums, the invention of alphabets, the electronic transmission of code, and the origins of information theory. He turns his vast learning on the current internet age, with an explication of news feeds, tweets, and blogs. This is a title that is a good jumping off point, where I expect to be able to follow threads into places he may not have had the inclination or space to take them. He profiles key figures in the history information theory, Charles Babbage, Ada Lovelace, and Samuel Morse to name a few. I expect to take up this text with the idea of potentially tracking the allographic journey of a title that has its origins in our western oral tradition (say, the Iliad), through it’s written form, and perhaps posit it’s continued journey into new forms and models.

Ong, Walter J., and John Hartley. Orality and Literacy:the Technologizing of the Word. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013.

Walter Ong’s “Orality and Literacy” is a classic work of scholarship that interrogates the differences between the oral and written traditions within the western canon. He examines the change in thought and expression brought about by the introduction of physical, symbolic representations preserved by written records. Rhetoric is a primary focus of Ong’s investigation, and he examines the impact of rhetoric on the psychodynamics and consciousness of discourse. This work is organized as an introduction to a deep, complex history and draws on aspects of his other, more situated scholarly works. A fascinating aspect of his argument involves the notion of an “oral residue” that Ong argues exists in written texts. With essays like “Writing Restructures Consciousness,” “Print Space and Closure” and “Some Psychodynamics of Orality” Ong’s collection is a classic on the social effects of oral, written, printed, and electronic technologies and the implications of their use for information gathering and sharing on philosophical, theological, scientific, and literary thought. I intend to examine this work for hints at not just the psychological and social effects, but also the implications for subjective impact on individuals from a formal, material perspective.

Passannante, Gerard Paul. The Lucretian Renaissance: Philology and the Afterlife of Tradition. The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

With The Lucretian Renaissance, Gerard Passannante provides a radical reinterpretation of the rise of materialism in early modern Europe. By charting the ancient philosophical notion that the world is composed of two fundamental opposites: Epicurean atoms, unchangeable and in motion in the void, as well as the void itself, Passannante points out that this philosophical system survived the Renaissance in transmission by a poem—”a poem insisting that the letters of the alphabet are like the atoms that make up the universe.” This philosophy of atoms and the void reemerged in the Renaissance as a story about reading and letters, materialized within a physical text. Drawing on the works of Virgil, Macrobius, Petrarch, Poliziano, Lambin, Montaigne, Bacon, Spenser, Gassendi, Henry More, and Newton, The Lucretian Renaissance “recovers a forgotten history of materialism in humanist thought and scholarly practice.” It also illustrates a unique scenario around what it means for a text(poem and philosophy) to change forms. This work will be useful for digital humanities scholars concerned with new media, materiality, and book archaeology.

Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

In The Marvelous Clouds John Durham Peters defines media rather broadly as “elements that compose the human world.” Although media in this way can be thought of as a sort of environment, Peters notes that the reverse can also be true, the environment itself forms a potential media. Drawing from ideas in media philosophy, he argues that media are the “infrastructures combing nature and culture that allow human life to thrive.”(4) Contemplating the many ancient and current, nearly universal means that people employ to sustain and bolster life, coping with the struggle to survive (navigation, farming, meteorology, Google) Peters shows how media lie at center of human interaction with the world.

In the introduction, Peters writes “’Media,’ understood as the means by which meaning is communicated, sit atop layers of even more fundamental media that have meaning but do not speak.” The truth value in this statement ultimately hinges on the meaning of “meaning.” “If we mean mental content intentionally designed to say something to someone, of course clouds or fire don’t communicate [meaning]. But if we mean repositories of readable data and processes that sustain and enable existence, then of course clouds and fire have meaning.” And they are part of an ecosystem of interdependencies for human generated meaning.

Ralph W. Gerard, “Some of the Problems Concerning Digital Notions in the Central Nervous System,” in Cybernetics: The Macy Conferences 1946-1953. The Complete Transactions, ed. Claus Pias (Zürich: Diaphanes, 2016 [1950]), 171–202.

Ralph Gerard, in his lecture at the Cybernetics Macy Conferences, which is a dated but classic transcription says “To take what is learned from working with calculating machines and communication systems, and to explore the use of these insights in interpreting the action of the brain, is admirable; but to say, as the public press says, that therefore these machines are brains, and that our brains are nothing but calculating machines, is presumptuous. One might as well say that the telescope is an eye, or that a bulldozer is a muscle.” Examining this text is useful when considering notions around materiality in human computer interaction, and, specifically, concerns surrounding the form and dissemination of knowledge within scholarly communications. My intention is to interrogate Cybernetic theory from the perspective of book culture, and materiality.

Zielinski, Siegfried. Deep Time of the Media: toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means. MIT, 2005.

Deep Time of the Media examines the hidden historical record of media developed for hearing and seeing. Siegreid Zielinsky makes the argument that technology did not proceed seamlessly from primitive tools to complex machinery, and it’s the same for the evolution of tools created for the human senses. Pulling from an abundance of original sources over 2000 years of the cultural historical record, Zielinski interrogates a variety of technologies in an attempt to illuminate the newness of old technologies. Some examples: a theater of mirrors in sixteenth-century Naples, a 17th-century automaton for musical composition, and the eighteenth-century electrical tele-wiring machine of Joseph Mazzolari. This book’s value is manifold but one of its particularly valuable qualities is its historical reach. Zielinsky unearths a host of unknown philosophers, visionaries, and inventors who are likely precursors to the modern media landscape. This work will be useful in discovering pockets within the media archaeology canon that can be generative for future media studies.