AFFECT RESEARCH IN THE DIGITAL HUMANITIES

When I began research for this bibliography, I was hoping to find explicit discussions on users affectual responses to technology, especially new technologies, and how those should or should not be considered when doing digital humanities projects. I was not able to find much in that meta-theoretical area, which could absolutely be due to my research skills, but may be indicative of an under-explored area of the field.

What I was able to find were accounts of specific digital humanities projects or research that either used or discussed affect as part of their work. There was also less in this area than I was hoping for, although I suspect that there may be scholars who are actually looking at affect, but are using different words, or directories that are not always including it in the metadata, which makes it difficult to search for without looking through every single digital humanities project.

I was interested by many of the articles that I found, and genuinely excited about a few, and so I’m choosing to be excited about an area of entanglement that is rife with possibility for the future, instead of being frustrated by the lack or difficulty of what is currently available.

Buiani, Roberta. “Performing the Web: Negotiating Affect and Online Aesthetics.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol. 6, no. 1, Jan. 2014, p. 23699. Crossref, doi:10.3402/jac.v6.23699.

Buiani examines the work of The Sandbox Project, an art collective which aimed to have an online space that would not only act as a catalogue of the physical work done during “labs” or live interactive performance/art events, but that would function as an extension of that space where the digital projects would compliment and enhance the physical ones. Buiani investigates the difficulties of this project, including the lengthy time commitments required by digital projects, the feeling of “distance” from their audience that some artists felt in an online space, and the difficulty of translating affect from a physical space into a digital one. Buiani looks at affect both as an artistic preoccupation and a community based one, especially since the goals of the project were always intended to be as political as they were artistic.

The website for The Sandbox Project has become a static archive, and while Buiani explores all the reasons, logistical and otherwise, why that came to be she is most curious about whether artists and users pre-existing ideas about internet spaces created too much rigidity to make effective use of their website. “It follows that only a shift of perspective in what “online content” means in relation to the “lived world” might liberate the Sandbox project from it’s own impasse” (13). Although they were not ultimately able to achieve what they wanted to with their digital project, the experiment raises a lot of interesting questions about digital and physical performance spaces.

Cocciolo, Anthony, and Debbie Rabina. “Does Place Affect User Engagement and Understanding?” Journal of Documentation, vol. 69, no. 1, 2013, pp. 98-120. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/docview/1268758130?accountid=7287, doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/10.1108/00220411311295342.

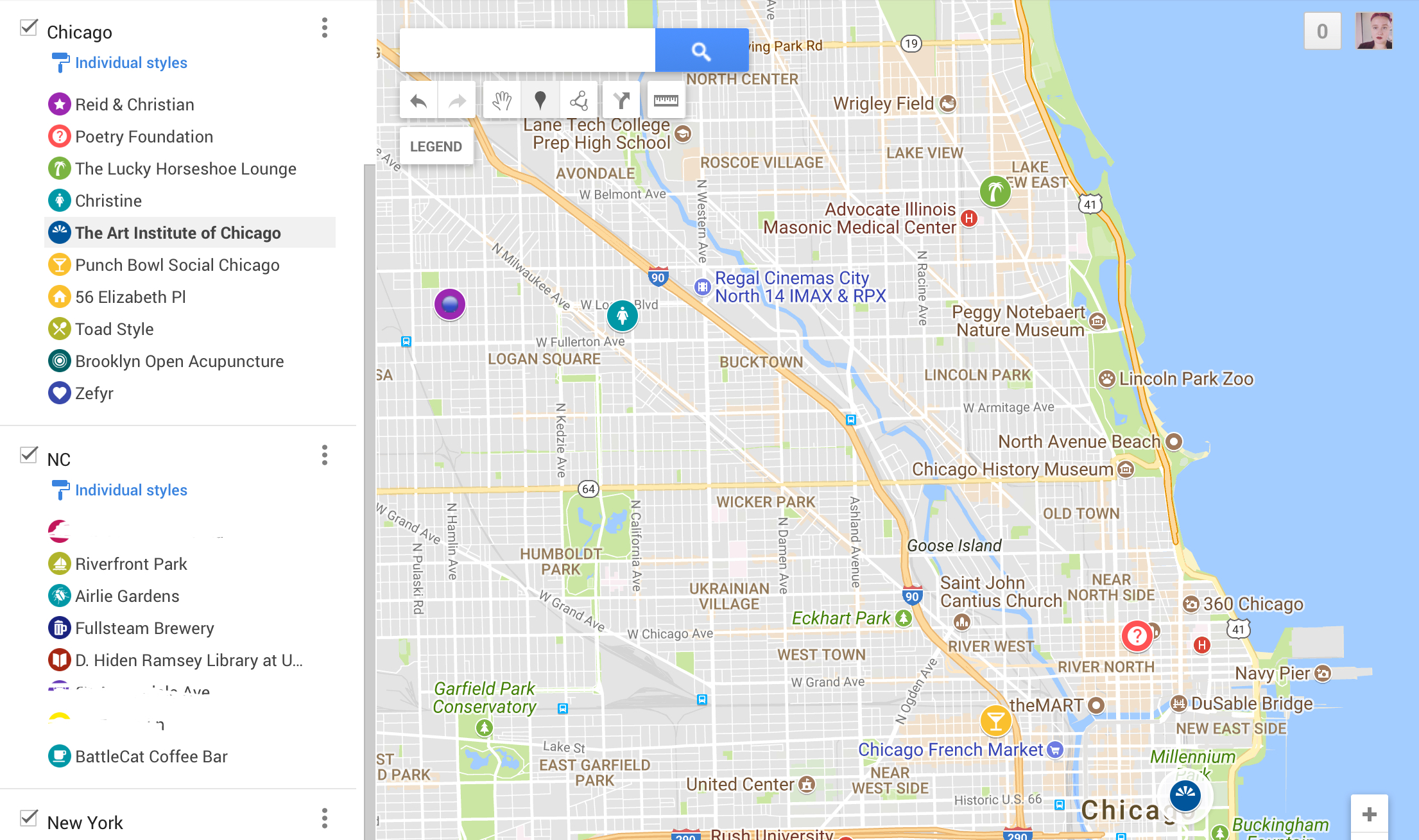

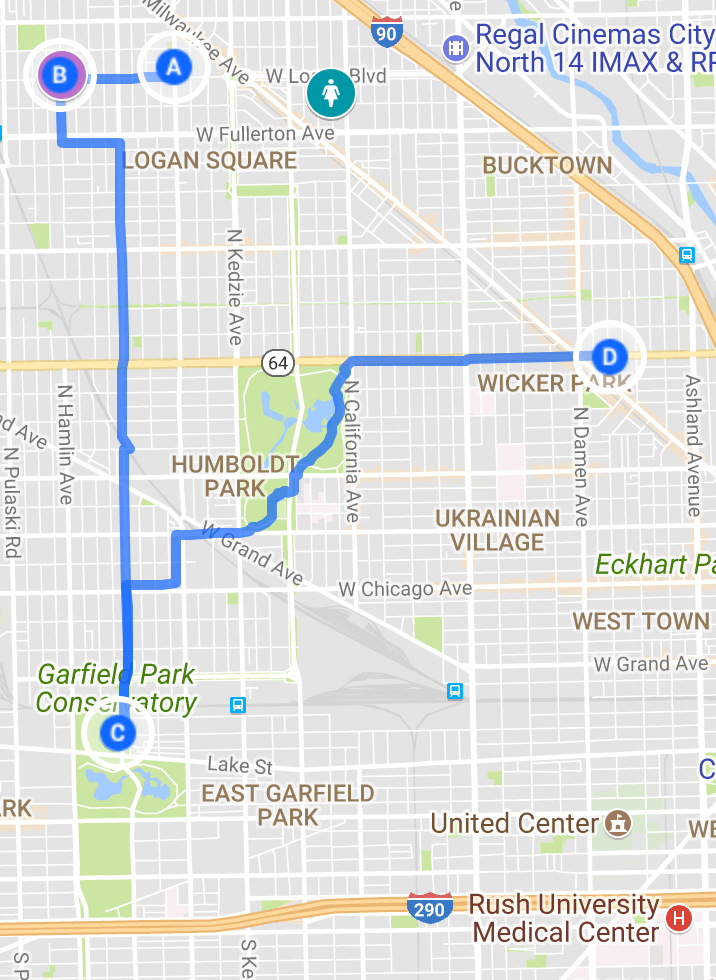

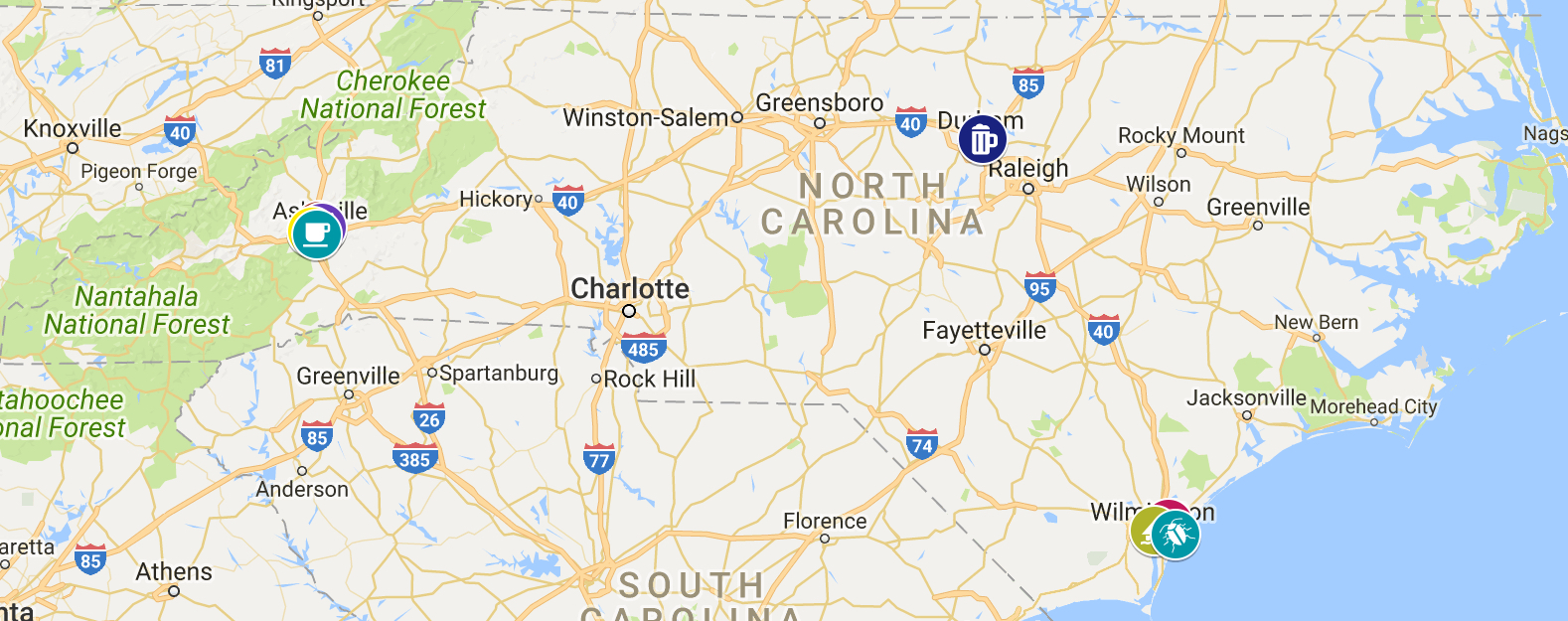

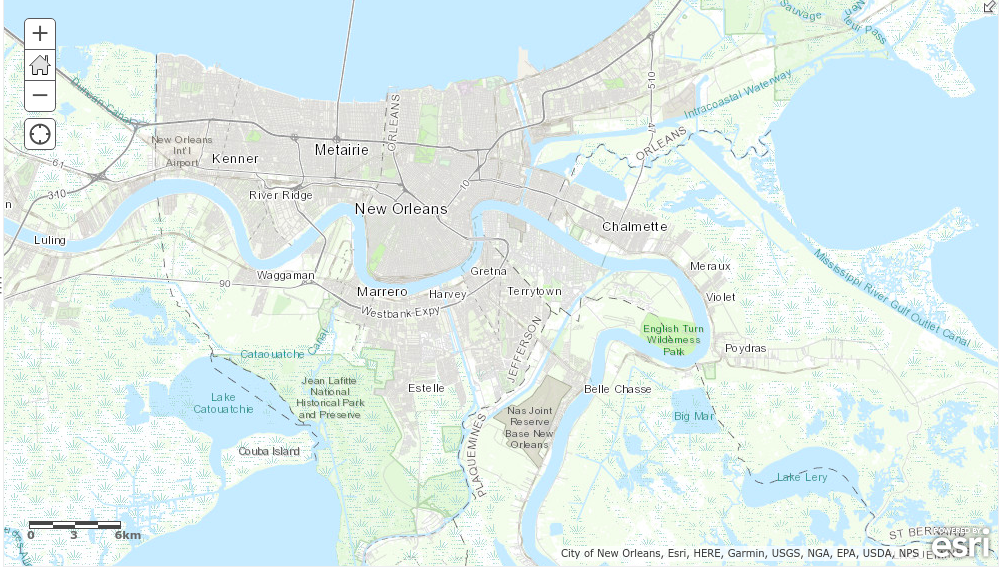

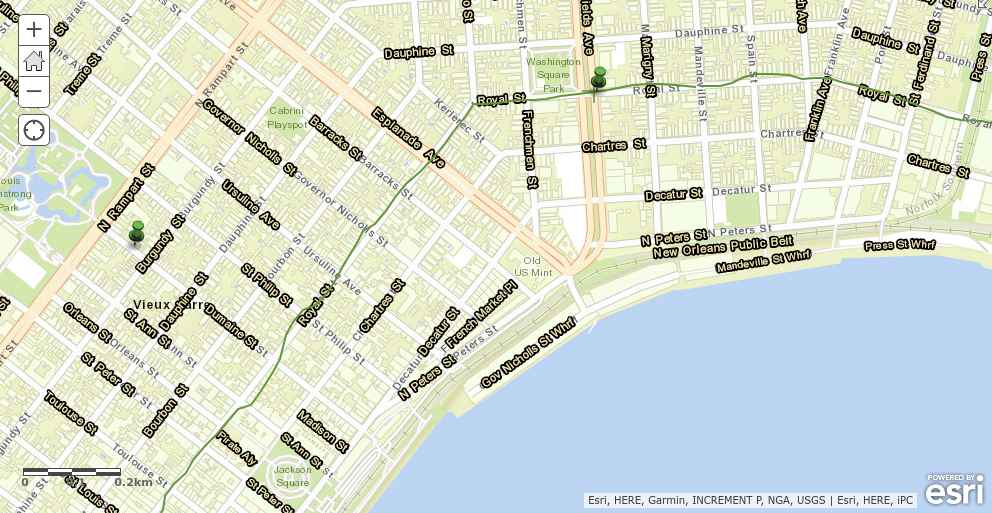

A case study of an educational mobile app, GeoStoryteller, which gives interactive educational guided tours of New York City, focusing on a specific historical story (such as German immigrants). The app uses cellphone technology to give the users videos, stories, and historical facts as they become physically present in a space. The idea was to see whether or not being physically present in a space enhanced or aided the learning process for the users. After testing, the researchers (who wrote the article and developed the app) were satisfied that being physically present in a space does enhance historical learning. While the article doesn’t discuss affect directly, the questions the researchers are asking are ones that are concerned with the affectual responses of users of a digital humanities project. The user responses that they were the most pleased with were the ones where the user not only felt like they had come away with some kind of “knowledge,” but with an emotional experience directly connected to the use of the technology.

Deng, Liqiong, and Marshall Scott Poole. “Affect in Web Interfaces: A Study of the Impacts of Web Page Visual Complexity and Order.” MIS Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 4, 2010, pp. 711–730. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25750702.

I included this article as an example of the type of academic writing concerning web affect that I came across most frequently: authors concerned with web marketing and web design for consumer use. This article is specifically interested in affectual responses to order and complexity on websites. It’s a highly technical analysis measuring users emotional responses (specifically “pleasure” and “arousal”) to different amounts of visual complexity in web design. The study found that users responded positively to a complex visual design, even more than a strictly efficient functional one, and that those feelings would carry on as they went further “in” to their website use. While this has potentially interesting humanities applications, the goal with this study is obviously purely commercial and consumer driven.

Graefer, A. (2016), “Reading” Through the Skin: Lady Gaga’s Online Representation and Affective Meaning‐Making. J Pop Cult, 49: 522-540. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12424

Graefer uses this article to do a highly personal affective reading of celebrity gossip blogs; specifically looking at articles about pop singer Lady Gaga. She is particularly interested in the concept of “skin”, taken from various media scholars, the idea that our relationship to any visual media is a tactile one and affective one, and not just a conversation between a recording eye and a processing brain. Graefer believes the concept of skin is especially useful for discussing affect and online media, because it’s a media whose pace and gaze we control through our touch, via a mouse or trackpad. This creates a responsiveness that can create specific affective responses. She is concerned not only how these gossip websites look, but how they make her feel.

I would be interested to see this kind of thought and analysis extended to digital humanities projects; to consider not only how to best represent information digitally, or look for information digitally, but how digital humanities projects can play with or replicate the affectual experience of the text that they’re analyzing.

Gregg, Melissa and Gregory J. Seigworth “An Inventory of Shimmers”. The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg, and Gregory J. Seigworth, Duke University Press, 2009. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cunygc/detail.action?docID=1172305.

The beautiful introduction to The Affect Theory Reader, Gregg and Seigworth outline how they understand affect theory as it stood at the time of their writing it, as well as what they believe to be the potentiality of the theory. They do not discuss the digital humanities by name in this introduction, but several of the eight “regions of investigation” that they lay out are areas that intersect if not completely entwined with digital humanities work (7). Most specifically, the sixth region, “that can be seen in various (often humanities-related) attempts to turn away from the much-heralded “linguistic turn” “ which calls up images of Moretti’s distance reading, amongst other foundational digital humanities texts. This is a thorough, and wonderfully written tour around the ideas that affect theory embraces.

Landsberg, Alison. “Theorizing Affective Engagement in the Historical Film.” Engaging the Past: Mass Culture and the Production of Historical Knowledge. Columbia UP, 2015. MLA International Bibliography, https://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/N2812963610/MLA?u=cuny_gradctr&sid=MLA&xid=980396cb. Accessed 29 Apr. 2018.

At the beginning of this chapter, Landsberg lists common critiques of historical films, all of which have also been lobbied against Digital Humanities projects. “That it inevitably “dumbs down” historical events, reduces the complexity of the past, and lacks the rigor of written history” (27). Landsberg uses the concept of affect to combat these claims, expanding on the work of Robert Rosenstone who posited that the formal elements of a move could make up “another kind of data,” that was as valuable as traditional historical research. “Like Rosenstone,” Landsberg writes, “I do not mean to dismiss written history or the purposes it serves but rather to suggest the specific power of a sensuous, experimental medium such as film to disseminate alternative but no less instructive forms of knowledge about the past” (29). Landsberg sees affect as a key tool in understanding the capacity of historical film as “another data”. She views the affective responses viewers have to historical cinema not only as engagement, or identification, but as a mode of knowledge through which they can come to have new understanding about history.

Losh, Elizabeth, et al. “Putting the Human Back into the Digital Humanities: Feminism, Generosity, and Mess.” Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis; London, 2016, pp. 92–103. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt1cn6thb.13.

This article works as a good state of the field report of feminist movements in the digital humanities in 2016. The authors discuss the work of collective FemTechNet, amongst other scholars addressing feminist concerns in the digital humanities. They assert that there needs to be a refocusing on not only overtly gendered modes of discourse, but to also embrace modes such as affect, embodiment, and critical “mess,” which tend to be queer/feminine modalities even when they aren’t specifically gendered.

Nowviski, Bethany. “What Do Girls Dig?” Debates in the Digital Humanities Created April 7th, 2011. Accessed April 29th 2018. http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/1

Sparked by a conversation on twitter, (the article is written using Storify, which allows users to archive and order tweets into a narrative), Nowviski dives into the possible reasons why women are a scare presence in textual data mining. One of the reasons she thinks likely, and which she states is true for herself, is the rhetorical language used around data mining, which makes it appear very tech heavy, and not in line with the more “interpretive” forms of digital humanities that interests her. She widens the scope of this question to invite a larger conversation about how the rhetorical language we use may be inadvertently causing gender disparities in certain parts of digital humanities study.

Oppermann, Matthias. “Digital Storytelling and American Studies: Critical Trajectories from the Emotional to the Epistemological.” Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, vol. 7, no. 2, 2008, pp. 171-187. MLA International Bibliography, https://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/N2812682908/MLA?u=cuny_gradctr&sid=MLA&xid=9906690e. Accessed 29 Apr. 2018.

In this article, Oppermann defines an affective dimension of learning as “their own voice and opinion”, them referring to students (177). He believes that digital storytelling, multi-media personal/historical storytelling projects, can be a way to combine affective and cognitive (outside stories and facts) learning in a way where the dimensions enrich one another. By positioning their own personal stories in the same context as the historical or cultural areas that they are studying, Oppermann believes students can see the academic conversation more clearly, and feel more empowered to become a part of it.

Rice, Jeff. “Folksono(Me).” JAC, vol. 28, no. 1/2, 2008, pp. 181–208. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20866831.

Rice begins this article by introducing Bob Dylan’s famous turn to electric instrumentation at the Newport Folk Festival as a framing device through which to look at the ways in which rhetorical categorization and pedagogy has embraced or rejected digitalization. When Dylan shifted from acoustic to electric instruments and still called it folk, while also widening the lyrical scope of what topics folk music could include, Rice argues that he created an affective experience (one that folds in the enraged audience reaction, and the sheer power of the music he played) which shifted the category of “folk” to include new definitions. The shift in the humanities and pedagogy to digitalization, he argues, is similarly using affective experience to not create new categories, but to enable a widening or shift of categorization.

The fold of affect into taxonomy is a method called Folksonomy. It includes open tagging systems (bookmarks, or hashtags), and lets users categorize things based on their own intuition instead of by a premarkated system. Rice combines this idea with digital technologies that allow for a combination of written/audio/visual mediums to create a new form of rhetorical writing that he calls Folksono(me), where the author is placed centrally within a remixed and highly personally referenced set of categorizations.